EUR

en

Centrifugal slurry pumps are widely used to transport mineral slurries. Under certain operating conditions it is possible for the flow through the slurry pipeline to reduce to low or zero flowrates. Slurry particles will therefore settle out and in the worst case it is possible that they block the slurry pump intake and discharge branches. If the slurry pump continues to operate in this condition, the energy input to the water inside the pump causes the water to heat and generate steam. The pressure build-up from the steam can lead to a potentially dangerous situation and may result in the pump exploding. The causes of blocked pipelines will be reviewed to assist with the understanding of the hazards involved. Some laboratory pump test results together with field experience will be discussed in relation to what can be changed to reduce the risk and to assist in overcoming the hazards.

The majority of slurry pumping applications occurs in the mining and dredging industries. Slurry is defined as any mixture of solid particles and a fluid (normally water). Slurry properties and particle sizes vary greatly from low to high concentration and from silt to gravel sizing. The transport of solids in the form of slurry in pipelines using centrifugal slurry pumps is common practice. Slurry is typically mixed before entering the centrifugal slurry pump but as it travels along a pipeline, the velocity gradient in the pipe and/or the slope of the pipeline can change causing density gradients within the pipeline. As the solids start to settle, the particles become stationary on the bottom of the pipeline causing stationary dunes or even plugs to form. The plugs in the pipeline can partially or totally block the pipeline causing the flow through the pipeline to decease to very low flows and in the worst case to drop to zero. In this case the pipeline can become totally plugged with solids requiring splitting the pipe joints to clean out the solids. Shou (1) details the various conditions that plugs may form in a slurry pipeline and concludes that while it is possible to design the slurry system to minimise the occurrence of blockages, the risk of blockage cannot be entirely eliminated. There are generally different causes of blockage such as: Operation of the pipeline at subcri tical velo city ie at a velocity less than the settling velocity of the particle sizes in the slurry. High solids concentration above system design. Large d ebris eg large p ieces o f rubber such as conveyor belting or tramp metal. Pipeline starting and stopping. Pipe liner collapse. Reducing pump speed below a level that causes particles to settle out in the pipeline. Inadvertent closing of both the intake and discharge valves on the pump blocking all flow. Shou (1) provides design considerations to prevent blockage. The first precaution is to establish the minimum settling velocity based on the coarsest particle distribution and not the mean. A second precaution is to size the variable speed drives of centrifugal slurry pumps to allow the pumps to be sped-up to assist in unblocking the pipeline. When blockages occur, there is the immediate hazard that the centrifugal slurry pump(s) will be operating at very low or zero flow.

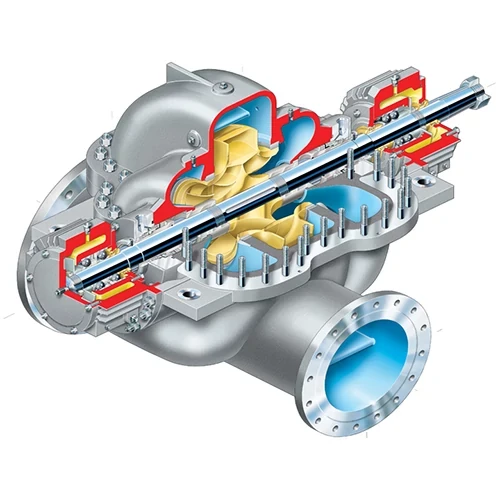

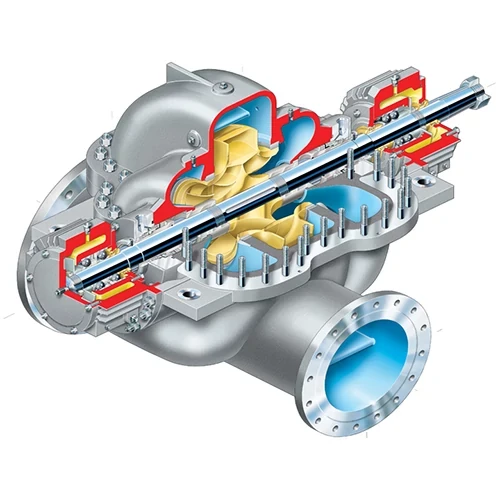

Slurry pumps are traditionally manufactured from castings and are lined with hard metals (with low fracture toughness) or elastomer. Lined pumps have an outer ductile casing which supports the internal pump pressure loads as well as piping loads. The outer casing is normally bolted together along a vertical joint line. The lined pump is therefore superior in withstanding pressure loads as its strength is not diminished by wear from the slurry particles or dependent upon the liner material as the casing does not require a wear or corrosion thickness allowance. Complete information on pump explosions is difficult to find. O’Connor (2) provides some case histories. However, the effects apart from the obvious damage to property and loss of production, is that explosions can lead to personnel injury and in a very few cases death. This is the result of a large percentage of the driver power going to heat the fluid inside the pump which turns to steam once the temperature reaches 100 C. The pressure can then rapidly rise, leading to either failure of the casing bolts and/or the pump casing. The sudden release of energy during bolt or casing failure can produce projectiles that can be thrown reportedly up to 100 m. In other cases, the loads are sufficient to wrench the pump and/or drive from their foundations. The release of superheated steam and slurry can cause serious injuries. To determine the temperature and pressure rise in a pump with zero flowrate, tests were conducted on an 8/6 pump with intake and discharge flanges blanked and the pump half filled with water and then run at 900 r/min. Figure 1 shows that the final temperature reached was approximately 200 C at which time the pressure was 2,100 kPa. The time was approximately 45 minutes in total with the first 25 minutes the temperature was below 100C. This time is typical and correlates well with other test work in (2). One can conclude that from the time of blockage, the risk of catastrophic failure is already high after only 10 to 15 minutes of operation at zero flow. Consequently any countermeasures need to have a fast response time and be activated to shut-down the pump within this time period. Actual calculation s of pressure rise need to take into account the liquid properties of specific heat and change of vapour pressure with temperature. Processes that use high temperature such as Alumina slurries at 100 C would reach critical temperature and pressure much faster than water slurry at room temperature. Normally the larger the volume of fluid in the pump, the slower the temperature rise. Experience has shown that the loss of pressure at the pump seal or at liner joints is normally far less than the rapid rise once the fluid turns to steam. The major types of measurement which can be utilised to monitor and / or control temperature rise and pressure are listed in Table 1. Out of the possible means, monitoring the temperature rise provides one of the most reliable for reducing the risk of pump explosion.

To ascertain the risk of any pump exploding, it is necessary to review all the hazards associated with the application, system, pipeline, system controls and type of pump construction. Assigning numerical values to the quantities in the following equation, it is possible to calculate a relative risk rating for each pump. Risk Rating = Consequence x Frequency x Probability The risk rating can be compared to historical data and suitable strategies to minimise the risk rating can be established. Weir Warman has been working with end users and can assist with two risk minimisation devices that can be used either independently or combined.

A thermal cut-out device is mounted through the pumps outer casing to measure the temperature on the outside of the metal liner (Figure 2). The device can be set to cut-off the electric current to the motor at a safe temperature before the pressure rises to a critical level. WARNING: Once tripped and the pump is stopped, the pump should be allowed to cool down before attempting to dismantle. Extreme care is required as the pump may contain high pressure liquid and steam which can only be released once the pump is opened.

A range of Warman metal lined slurry pumps have been fitted with a pressure relief failure ring mounted at the back of the shaft seal chamber (Stuffing Box, Expeller Ring or Mechanical Seal Adaptor). The pressure acting over the large area of the seal chamber causes a high-force on the shear lugs on the failure ring. The ring is designed to fail in shear at a pressure of approximately 1.2 times higher than the pumps maximum allowable working pressure (MAWP). As a pumps test pressure is normally 1.5 times the MAWP, the failure occurs at a safe pressure. The ring fails allowing the O-ring seal between the end of the seal chamber and the back liner in the pump to fail, thereby allowing fluid, steam and slurry to escape out the back of the pump. The escaping fluid and steam is contained within the pump by guarding and discharged downwards to the ground between the pump casing and the base. As the failure of the ring occurs at a safe pressure, the pump components are in no danger of failure or explosion. The failure ring should eliminate the risk of explosion if the thermal cut-out device is not fitted or does not function as intended, and all other signs or means are not activated ie the failure ring is designed as a passive safety device. Figure 3 shows the sequence of events as the pressure relief ring fails and the pressure is relieved. The failure ring must be replaced before the pump can be put back into service.

Advances in the application and range of thermal cut-out and pressure relief (passive safety) devices will assist to reduce the potential risks of pump explosion. These devices are simple and applicable to a wide range of applications. Further development is being undertaken to make these devices applicable to rubber lined pumps.

Bookmark

Daniel Féau processes personal data in order to optimise communication with our sales leads, our future clients and our established clients.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.